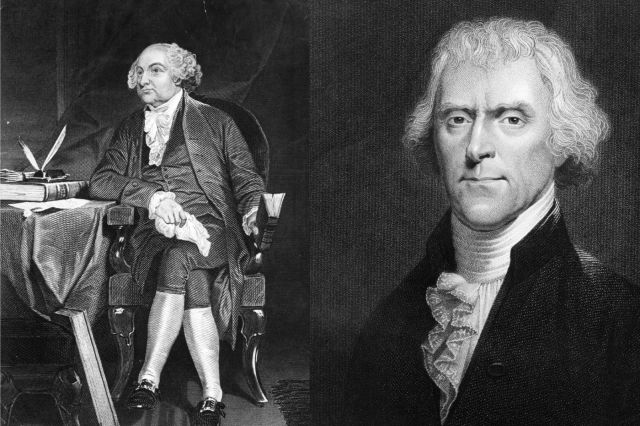

1800: John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson

If anything proves that partisan politics and electoral machinations are nearly as old as the United States itself, it’s the election of 1800, when Federalist Party incumbent President John Adams sought reelection against Democrat-Republican Vice President Thomas Jefferson. The already-bizarre premise of opposing parties holding the presidency and vice presidency was made possible at the time by a law stipulating that the presidential candidate who earned the second-most number of electoral votes became Vice President. In the election of 1796, Jefferson lost the presidency to Adams by only three votes, and the 1800 election was a rematch between the political rivals.

That time, with another narrow margin likely, both parties turned toward influencing electors, whose votes decided the winning candidate in states where there was not yet a popular vote. Jefferson wrote of his intent to sway electors in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey in a letter to James Madison. Federalist Senator Charles Carroll accused Jefferson and his supporters of also attempting to use “arts and lies” to manipulate votes in Federalist-leaning Maryland. From there, the accusations, well, escalated. Jefferson-supporting pamphleteer James Callendar claimed that John Adams was a hermaphrodite. Federalist newspapers accused Jefferson of maintaining a harem at Monticello.

When the votes were finally cast, the election ended in a tie between Jefferson and… his intended running mate, Aaron Burr. How? Each elector had two votes to cast, but there was no distinction at the time between a vote for President versus a vote for Vice President. Casting one vote for Jefferson and one vote for Burr was in effect a vote for each as President. The Constitution called for resolving this tie between the Democrat-Republican candidates with a vote in the House of Representatives, which was controlled by, you guessed it, the Federalist Party.

The task at hand was to vote on who, between Jefferson and Burr, would be President, but the Federalists saw an opportunity to seize power, either by delaying the proceedings past the end of Adams’ term, or attempting to invalidate enough votes to give Adams the majority. Others advocated for supporting Burr. Between February 11 and February 16, 35 rounds of voting took place, each ending in deadlock. Finally, after much lobbying by Alexander Hamilton against Burr, the 36th ballot resulted in Jefferson being appointed President. In the wake of the turbulent election, the 12th Amendment was ratified in order to prevent a repeat ordeal in 1804.