Dwain Northey (Gen X)

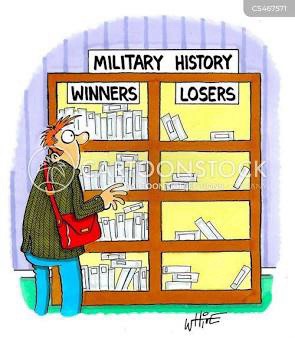

The phrase “history is written by the victors” underscores a fundamental truth about the construction of historical narratives: those in power often shape the story to serve their interests. When conflicts are resolved or empires rise, the prevailing side tends to document events in ways that validate their actions, justify their ideologies, and marginalize or erase opposing voices. This process results in a selective memory of the past, where inconvenient truths are downplayed or ignored altogether.

Victorious nations or groups often portray themselves as righteous, heroic, or civilized, while depicting their enemies as barbaric, evil, or misguided. For example, colonial powers historically framed colonization as a civilizing mission, omitting the violence, exploitation, and cultural destruction inflicted on indigenous populations. Similarly, wars are often recorded with emphasis on valor and sacrifice from the victor’s perspective, while the suffering of the defeated is minimized or vilified.

This manipulation can occur not only in official histories and textbooks but also in monuments, museums, media, and education systems. By controlling the narrative, the victors influence collective memory and identity, often sustaining national myths or legitimizing political power. As a result, generations may inherit skewed or incomplete versions of the past.

However, alternative histories—told by the oppressed, the colonized, or the defeated—often challenge dominant accounts. These counter-narratives seek to recover lost voices and provide a more balanced understanding of events. In recent years, efforts to decolonize history and amplify marginalized perspectives have gained momentum, highlighting the importance of questioning whose story is being told and why.

Ultimately, history is not a fixed set of facts but a dynamic, contested terrain shaped by power. Understanding this helps us critically engage with the past and recognize the influence of narrative in shaping our present and future.