Dwain Northey (Gen X)

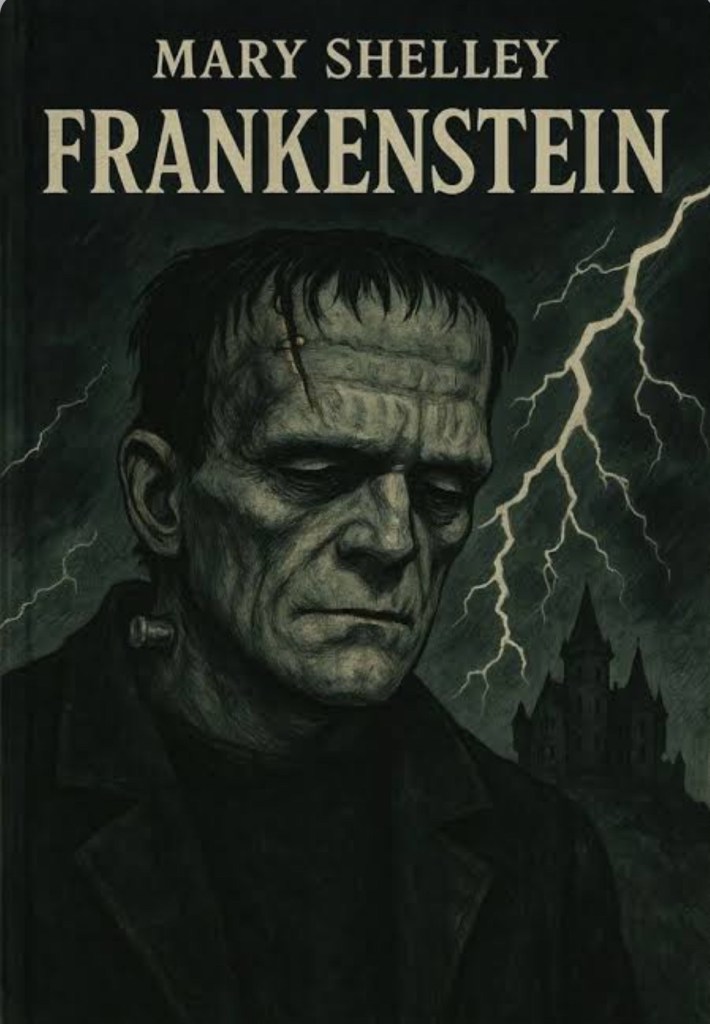

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was never meant to become the plastic green giant lumbering down the aisles of every Halloween superstore — yet here we are. What began in 1818 as a chilling philosophical meditation on ambition, science, and the fragile line between life and death has evolved into a cultural mascot of spooky season — complete with neck bolts, flat-top head, and a permanent look of mild confusion.

Shelley, writing in the glow (and occasional flicker) of the Enlightenment, was wrestling with humanity’s swelling ego — the idea that with enough electricity and curiosity, we might just snatch life itself from the hands of nature. Her Dr. Victor Frankenstein wasn’t a mad scientist in a crumbling castle surrounded by lightning rods; he was a young idealist, a scholar obsessed with the boundaries of human knowledge. And his creation — the “Creature,” as Shelley deliberately called him — was not the grunting monster of later films but an articulate, tragic figure who only turned violent after society rejected him. The real horror in Shelley’s story wasn’t the creature’s patchwork face; it was the mirror it held up to human arrogance and moral negligence.

Fast forward a century, and Hollywood took that elegant Gothic novel and gave it the Universal treatment — thunder crashes, villagers with torches, and Boris Karloff rising from the lab table with a moan that shook the silver screen. By 1931, Shelley’s tragic meditation had been stitched together into pop culture’s most recognizable monster. The Creature lost his eloquence but gained marketability: green skin, heavy boots, and a trademark groan that could be sold as a Halloween costume.

By the mid-20th century, Frankenstein’s Monster had gone from symbol of moral overreach to misunderstood party guest. He’s danced with Dracula, shared screen time with Abbott and Costello, and even taught children on The Munsters that being different isn’t all that bad. Somewhere along the way, Shelley’s nightmare warning about playing God became the friendly neighborhood face of “spooky but safe.” The lightning that once sparked a philosophical horror now powers inflatable lawn decorations.

Yet, in a strange way, that transformation feels fitting. Frankenstein was always about humanity’s compulsion to create — to animate the inanimate, to bring dead matter to life. In turning Shelley’s intellectual horror into a seasonal icon, we’ve done exactly what her story predicted: taken something profound and breathed artificial life into it until it lurches, glowing-eyed, through our modern world. We’ve reanimated Frankenstein himself.

So when you see that grinning green face this Halloween, maybe spare a thought for Mary Shelley — 18 years old, staring at the firelight, conjuring not a monster, but a warning. A warning that, two centuries later, we still haven’t quite learned to heed.