Dwain Northey (Gen X)

Every Halloween, when the moon hangs fat and pale and the wind mutters secrets through half-dead trees, one name inevitably rises from the grave: Dracula. No matter how many times we drive the stake, no matter how many times Hollywood “modernizes” him with slick hair and leather pants, the old Count just keeps coming back. He’s the pumpkin spice latte of horror — seasonal, enduring, and just a little overindulgent — yet undeniably irresistible.

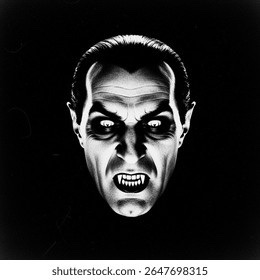

But before he was the suave Transylvanian aristocrat in a velvet cape, he was Nosferatu, the rat-faced plague of shadows who brought nightmares to life in F. W. Murnau’s silent 1922 classic. Max Schreck’s gaunt, skeletal creature was less lover and more leper — a crawling disease that spread through Europe’s veins like death itself. Nosferatu wasn’t about seduction; he was pestilence wearing human form. That first cinematic Dracula was born not of romance but of fear — the fear of the unknown, the foreign, and the things that skitter just out of sight.

Then came Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and the monster gained a title, a home, and a taste for dramatics. Stoker’s 1897 novel married Gothic excess with Victorian repression — sex and sin draped in lace and fog. His Count was a corrupted noble, a fallen angel with an Eastern European accent, a cautionary tale about what happens when desire and decay dance too close. Dracula was both warning and temptation, a mirror held up to a society terrified of its own hunger.

And if we trace him back further — peel away the myth like so much decaying flesh — we find Vlad III of Wallachia, or Vlad Țepeș, the Impaler himself. The man who allegedly dined among forests of skewered enemies, his goblet raised in toast to the writhing symphony of human suffering he’d composed. Historians still argue whether he was a patriot, a sadist, or a little of both, but one thing’s certain: no PR team in history has ever had to work harder to rehabilitate a legacy. Vlad didn’t drink blood — he spilled it. Yet through Stoker’s alchemy, this medieval warlord became the template for every undead seducer since.

Over the centuries, Dracula has evolved — or rather, metamorphosed. From Bela Lugosi’s hypnotic gaze to Christopher Lee’s feral elegance, from Gary Oldman’s tragic romantic in Coppola’s fever dream to the reflective antihero of Castlevania and What We Do in the Shadows, the Count has worn a thousand faces but kept the same gnawing emptiness at his core. He’s not just a monster — he’s a mirror. Every generation remakes Dracula in its own image, projecting onto him whatever we fear or crave most.

In the 19th century, he embodied sexual taboo.

In the 20th, he became the symbol of corrupt power — the aristocrat feeding on the masses.

In the 21st, he’s a tragic immortal, cursed by loneliness, haunted by what eternity costs.

We pity him now. The predator has become the victim, a misunderstood soul seeking connection in a world that has long since moved past candlelight and crypts. He doesn’t stalk villagers anymore — he swipes right. His coffin’s got Wi-Fi, and even immortality can’t save him from existential dread.

Yet beneath every reinvention, the same pulse of horror beats: the fear of what never dies. Dracula isn’t scary because he drinks blood. He’s terrifying because he’s us — our hunger for control, our obsession with youth, our inability to let go. He’s the embodiment of every selfish wish whispered at midnight: let me stay young, let me stay beautiful, let me live forever.

And so, as Halloween fog curls through our streets and little vampires beg for candy under plastic fangs, remember this — Dracula doesn’t lurk in the castle anymore. He lives in the reflection you avoid when the lights are low, in that part of you that wonders what eternity might feel like if it didn’t hurt so damn much.

The Count never died. He just learned to adapt.

And somewhere, in the shadows of every October night, he’s still waiting — charming, tragic, and forever thirsty.