Dwain Northey (Gen X)

It’s always entertaining to watch people insist that the Earth is flat — a giant cosmic pancake, apparently held together by vibes and conspiracy theories — while geologists quietly sigh and go back to studying the 4.5 billion years of evidence saying otherwise. These are the same people who think fossils are “tests of faith” and that maps are “government propaganda.” But here’s the plot twist that might truly bake their noodle: not only is the Earth round, it’s also restless. And once upon a time, all the continents we know today were fused together into one magnificent supercontinent called Pangea.

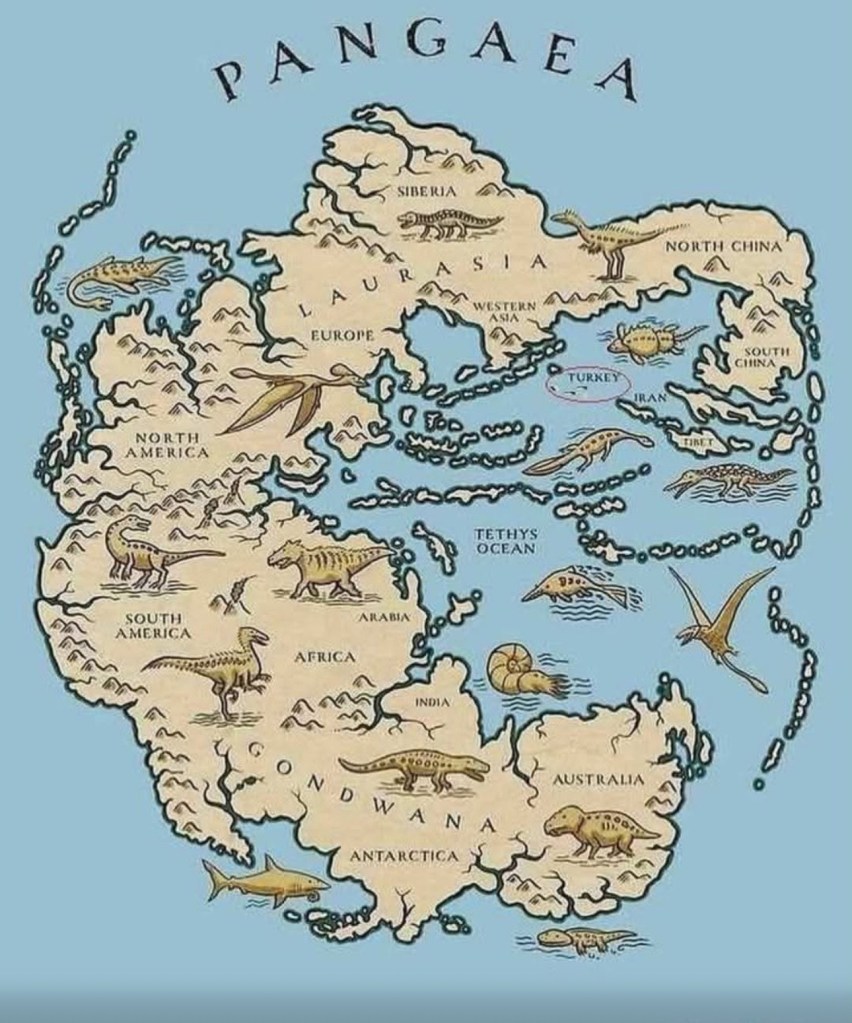

Yes, dear deniers, the world used to be one big, happy landmass — no passports, no borders, no arguments about who invented pizza. Just one sprawling continent surrounded by a vast ocean called Panthalassa. Around 335 million years ago, the tectonic plates of the Earth’s crust cozied up together to form Pangea, a sort of prehistoric mega-merge that made today’s map look like a jigsaw puzzle that hadn’t been shaken apart yet.

But Earth, as it turns out, is a bit of a drama queen. She doesn’t like to stay still. Beneath our feet, massive slabs of rock — tectonic plates — are constantly on the move, grinding, colliding, and drifting at about the same speed your fingernails grow. Over millions of years, these shifts tore Pangea apart like an ancient breakup that took eons to finalize. South America drifted away from Africa, North America broke up with Europe, and Australia floated off like a sunburned introvert heading to its own island party.

This grand tectonic tango is why we have earthquakes, volcanoes, and mountains. It’s also why the coastlines of continents — like the matching curves of Africa and South America — look suspiciously like puzzle pieces that used to fit together. It’s not a coincidence. It’s geology.

Of course, if you mention this to a flat earther, you’ll likely get a blank stare followed by something about NASA faking plate tectonics to sell globes. These are the same people who think gravity is “a hoax” but can’t quite explain why their shoes stay on the ground. The irony, of course, is that Pangea’s very existence is one of the strongest proofs that the Earth is round — because only on a spherical planet could such slow, circular drift patterns even occur.

Imagine trying to fit Pangea onto a flat Earth model. You’d end up with Madagascar hanging off the edge, Australia sliding toward oblivion, and Florida somehow upside down. The math doesn’t math.

The evidence for Pangea isn’t theoretical — it’s written across the planet’s bones. Identical fossils of plants and animals appear on continents now separated by oceans. Ancient rock formations in Brazil match perfectly with those in West Africa, like geological twins separated at birth. Even magnetic minerals in those rocks tell us that they once formed near each other before migrating across the globe.

But perhaps the most humbling lesson of Pangea is not just scientific — it’s philosophical. The continents we now treat as separate, competing entities were once literally one. The divisions that humans obsess over today — borders, nations, flags — are, in the grand timeline of the planet, temporary scratches on the surface of a restless, rotating sphere.

So the next time someone insists the Earth is flat, maybe smile and hand them a globe — not to mock them, but to remind them that the story of Earth is long, complex, and beautiful. The ground beneath us has traveled across oceans, crashed into mountains, and will keep moving long after we’re gone.

Pangea is proof that the world was once whole — and that change, not stasis, is the planet’s true nature.

And if that’s too much for the flat Earth crowd to handle, that’s okay. They can keep clinging to their map of the cosmic pancake. The rest of us will keep spinning, drifting, and evolving — just like the Earth has done for hundreds of millions of years.