Dwain Northey (Gen X)

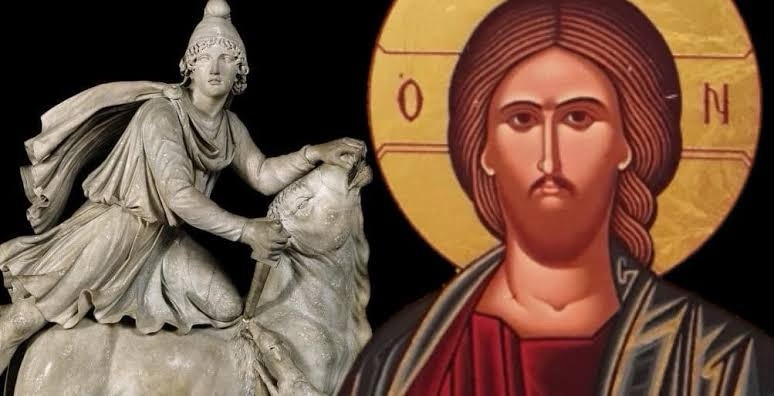

When people speak of ancient stories that seem to mirror the Christian nativity, they often point to the figure known in Indo-Iranian tradition as Mithra (or Mairii / Mairis in some linguistic reconstructions and regional variants). Though the surviving material about Mithra/Mithras is fragmentary and filtered through centuries of cultural transmission—from Indo-Iranian religion, to Zoroastrianism, to the Roman mystery cults—certain narrative motifs have invited comparison to the Christian story of Jesus.

The most striking parallel emerges in the Roman Mithraic tradition, where Mithras is described as being born from a rock (the petra genetrix)—a miraculous, non-human birth that signaled a divine arrival. Early Christian writers, encountering Mithraic iconography in the late 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, sometimes accused Mithraists of imitating Christian rituals, which ironically suggests they recognized competing narratives of supernatural birth and salvation circulating in the empire.

The possible Indo-Iranian antecedent—often referred to in modern scholarship as Mairis—is associated with themes of cosmic order, divine covenant, light, truth, and the defense of the righteous. In these traditions, the figure is portrayed as a mediator between the divine and human realms, a guarantor of moral order, and a protector of the faithful. These elements are not identical to the Christian nativity story, but they do establish a mythic framework into which a later audience might read similarities.

By the time the Roman world encountered Christianity, Mithras was widely venerated as a savior figure whose birth was celebrated around the winter solstice, whose followers reenacted ritual meals, and whose cult promised divine favor and eternal life. In the religiously competitive landscape of the late Roman Empire, overlapping motifs—miraculous birth, cosmic mission, divine sonship, and salvation—were not just common; they were expected. This made it easy for later commentators, and even some modern interpreters, to see the story of Mairis/Mithras as a kind of mythic “parallel track” running alongside the emerging Christian narrative of the Christ child.

Yet the parallels, while real in theme, do not form a one-to-one equivalence. The Christian nativity is grounded in a linear historical claim tied to a specific mother, time, and place, whereas the stories of Mairis and Mithras are rooted in symbolic cosmology and mystery-cult theology rather than biographical detail. The resemblance lies not in verbatim storytelling but in a shared ancient pattern: a world longing for a divine mediator, a bringer of order, a child of miraculous origin who signifies hope amid chaos.

In this sense, the tale of Mairis and the birth narrative of Jesus Christ are less examples of direct borrowing than they are evidence of a deep, cross-cultural human impulse—an enduring mythic grammar that echoes across civilizations whenever people imagine what it means for salvation, justice, or divine light to enter the world in the form of a child.