Dwain Northey (Gen X)

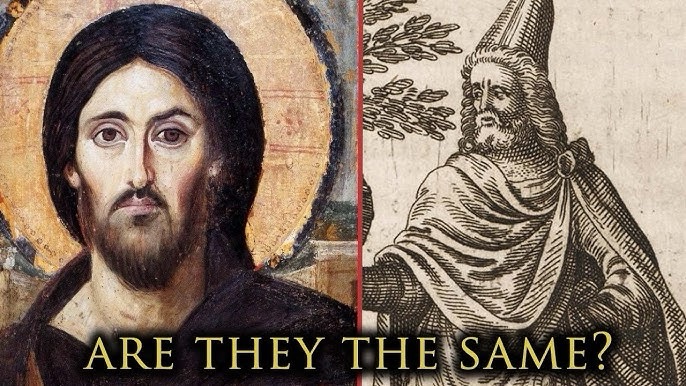

Across ancient religious traditions, cultures often shaped their gods and heroes around the same deep human longings—healing, resurrection, divine parentage, and the hope that suffering could be undone. In Greek mythology, Asclepius, the physician-god, embodied humanity’s desire to conquer death. In early Christianity, Jesus, described by believers not as a demigod but as God incarnate or God’s son depending on the theology, filled a remarkably similar symbolic role. When the two stories are placed side-by-side, the parallels become striking—not because one directly copies the other, but because human imagination tends to return to similar archetypes.

Divine Lineage

Asclepius is born of a mortal woman, Coronis, and the chief god Apollo, making him—within Greek terms—a demigod with divine gifts. His infancy is marked by drama: Coronis dies before his birth and Apollo rescues the child from her pyre, giving him over to the wise centaur Chiron to be raised.

The Jesus narrative, in Christian theology, is different in concept but similar in structure: he is born of Mary, a human woman, and the divine Father through miraculous conception. Though Christianity does not call Jesus a “demigod,” many outside observers have historically noted that the combination of divine paternity and human birth fits the broader ancient Mediterranean pattern.

The Healer Motif

Asclepius becomes the ultimate healer, taught every medical art, able to mend wounds, cure disease, and—eventually—raise the dead. This last power becomes his defining trait, the reason mortals flock to his temples and sleep in the abaton hoping to receive healing dreams.

Jesus’s story centers on healing as well: restoring the blind, curing the sick, raising the dead (Lazarus being the most famous example), and offering spiritual wholeness. His miracles elevate him beyond prophet or teacher—they mark him as a divine agent whose authority over life and death is absolute.

Both figures, in their traditions, are the embodiment of divine medicine: the idea that the divine directly intervenes to mend the broken.

A Death That Offends the Divine Order

Asclepius’s downfall comes because he takes his healing too far. When he begins resurrecting mortals, Zeus intervenes and kills him with a thunderbolt to preserve cosmic balance. The gods cannot allow immortality to spread unchecked.

Jesus, in Christian accounts, is executed not by divine decree but by earthly authorities; yet his death is still framed as necessary for a larger cosmic story. While Asclepius is struck down for reversing death, Jesus is killed so that death might be reversed for all believers.

Resurrection and Divine Elevation

After Asclepius is slain, Apollo protests, and the gods eventually restore Asclepius, raising him to full divinity. He becomes a god of healing, worshiped throughout the Mediterranean with serpent-entwined rods—symbols still used in medicine.

Jesus’s resurrection is the central miracle of Christianity: a divine validation of his message and identity. After rising, he ascends to sit at the right hand of God, an exaltation strikingly similar to the way Greek gods elevated a heroic figure into the heavenly realm.

Temples and Followers

Asclepius’s sanctuaries—Asclepieia—were healing centers where the sick sought cures through ritual, dreams, and the presence of the god. His followers spread across the Greek and Roman world, and many inscriptions record miraculous healings attributed to him.

Early Christianity likewise spread accounts of Jesus’s healing power, resurrection, and divine authority, building a community centered on faith, sacrament, and the hope of spiritual and physical salvation.

So What Do These Parallels Mean?

The similarities between Asclepius and Jesus don’t necessarily imply direct borrowing; instead they reveal a shared ancient archetype:

the divine healer, born in a blend of human and divine worlds, who conquers death and is ultimately exalted.

Humanity has always hoped for three things:

• that suffering can be healed,

• that death can be undone,

• and that a compassionate divine figure stands between human frailty and cosmic fate.

Asclepius embodied that hope for the Greeks. Jesus embodied it for early Christians—and still does for billions of people today.

Both stories, separated by culture but united by yearning, show how myth and faith evolve around humanity’s deepest fears and greatest dreams.