Dwain Northey (Gen X)

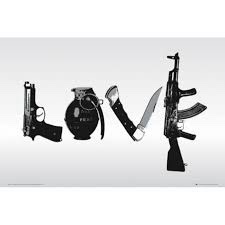

I saw a bumper sticker today that said LOVE, except it didn’t actually say love. It threatened it. The letters were spelled out with an AR-style rifle, handguns, and a grenade—because apparently in some deeply confused corners of America, the highest expression of affection is a catalog from a weapons manufacturer.

And I just stared at it, trying to understand what kind of moral gymnastics you have to perform to arrive at the conclusion that instruments engineered for the sole purpose of killing human beings are an appropriate font choice for the word love.

Love.

Not defense.

Not fear.

Not don’t tread on me.

But love.

That sticker didn’t say “I care about my family.” It said, “I confuse power with virtue.” It didn’t say “I value life.” It said, “My emotional vocabulary begins and ends with violence.” Because when you spell love with guns, what you’re really saying is that your vision of human connection is conditional, armed, and itching for a justification.

Let’s be very clear: guns are not symbols of love. Grenades are not metaphors for compassion. An AR rifle is not an abstract philosophical concept—it is a machine designed to efficiently end lives. That is its purpose. That is its job description. No amount of flag decals or cursive script changes that reality.

So when someone chooses those tools to represent love, what they’re actually advertising is not affection but paranoia. Not community but alienation. Not strength but fear so intense it needs to cosplay as toughness.

Because real love is vulnerable. Love is unarmed. Love requires trust, empathy, patience, and the terrifying act of not assuming everyone around you is an enemy. And for people who have built their entire identity around suspicion and grievance, that kind of love is unbearable. It’s much easier to love something cold, mechanical, and lethal—something that doesn’t ask you to grow or listen or care.

That bumper sticker wasn’t a celebration of love. It was a confession. A confession that somewhere along the way, we let marketing, politics, and rage rot a perfectly good word until it could be repurposed as a threat. Until love meant “agree with me or else.”

And that’s the saddest part. Not that someone owns guns. Not even that they like them. But that when asked—implicitly, by a single word—what love looks like, they answered with objects designed to make sure someone else never gets to experience it again.

That’s not love.

That’s a warning label.