Dwain Northey (Gen X)

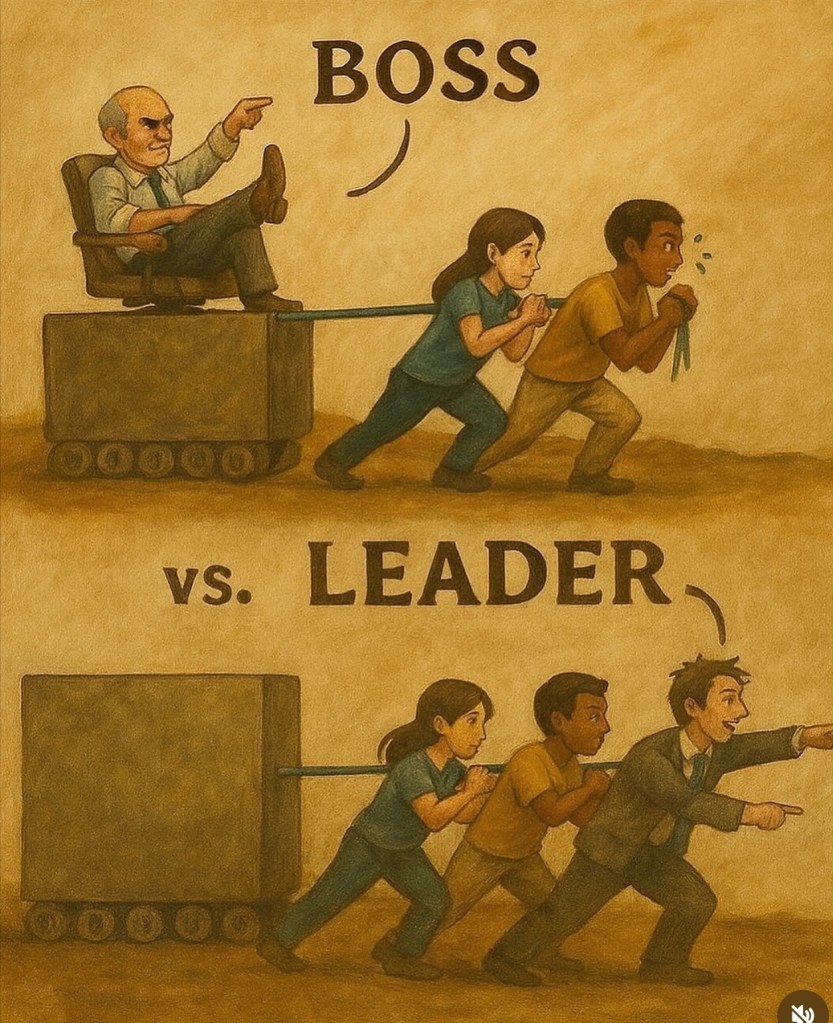

Somewhere along the corporate evolutionary timeline, we collectively agreed that if someone had a title, a calendar full of meetings, and the power to approve PTO, they must therefore be a leader. This is how we ended up with a surplus of managers and a famine of leadership.

Let’s clear up the apparently counterintuitive truth: most managers are not leaders, but many leaders end up being managers. The confusion comes from mistaking authority for influence and proximity to power for the ability to inspire anyone beyond quiet compliance.

A manager is, at their core, a systems operator. They manage processes, schedules, metrics, compliance, deadlines, and spreadsheets with colors that imply urgency. Managers ensure things happen on time, within policy, and according to whatever framework was introduced at the last offsite. None of this is inherently bad. In fact, good management is necessary. Planes should be fueled. Payroll should be accurate. The meeting should probably start at 10 if everyone was told it starts at 10.

But leadership? Leadership is something else entirely.

A leader shapes direction, not just execution. Leaders create meaning where there is none, clarity where there is confusion, and momentum where morale went to die sometime around the third “re-org.” Leadership isn’t about enforcing rules—it’s about earning trust. And that’s the problem: trust cannot be mandated, KPI’d, or auto-filled into a performance review template.

Most managers fail at leadership because management rewards control, while leadership requires vulnerability. Managers are promoted for hitting numbers, maintaining order, and not rocking the boat. Leaders, meanwhile, often rock the boat so hard they get water in their shoes—and then teach everyone else how to row.

This is why you can have a manager who has supervised people for twenty years and still has no idea how to lead them. They default to authority: “Because I said so,” “That’s policy,” or the timeless favorite, “My hands are tied.” These phrases may keep the org chart intact, but they kill engagement on contact.

Leaders don’t hide behind policy. They interpret it, challenge it, and occasionally take a hit so their people don’t have to. They listen more than they talk, and when they talk, people actually stop scrolling. Leaders don’t need to remind you they’re in charge—you can tell by the way people choose to follow them, even when no one is watching.

Now, here’s the twist: many leaders eventually become managers, often against their will. Organizations notice someone who motivates others, solves real problems, and makes chaos slightly less chaotic—and immediately reward them with a title, a bigger inbox, and six standing meetings that could have been emails. These leaders succeed as managers because they lead through the role instead of hiding behind it.

They still manage tasks, yes—but they also manage morale, context, and purpose. They understand that people are not resources, culture is not a poster, and “open-door policy” means nothing if walking through that door feels like career suicide.

So why do we have so many managers who can’t lead? Because we promote for technical competence and punish emotional intelligence. We measure output, not impact. We confuse being indispensable with being effective. And we still act shocked—shocked—when teams burn out, disengage, or quietly quit while updating their résumés.

Leadership isn’t about rank. Management isn’t about wisdom. One is a role; the other is a skill. When they overlap, organizations thrive. When they don’t, you get compliance without commitment—and a lot of people wondering why “nobody wants to work anymore.”

The truth is simple, even if it’s uncomfortable: anyone can be given the power to manage. Very few earn the right to lead.