Dwain Northey (Gen X)

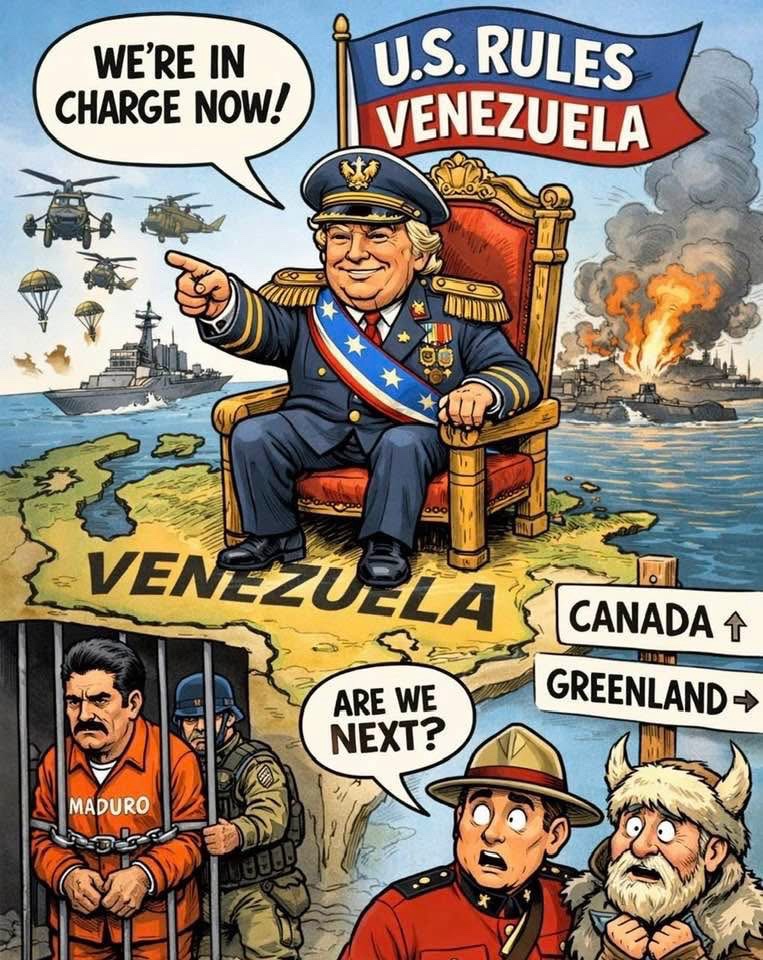

We are told, repeatedly and with great solemnity, that we have a peace-time president. The phrase is rolled out like a talisman, meant to ward off inconvenient questions, much like “thoughts and prayers” or “this hurts me more than it hurts you.” And yet, in the same breath, we are asked to accept that this very peace-time president authorized a SEAL Team to enter Venezuela, seize its sitting president, and spirit him away into custody. One is tempted to ask: at what point does peace begin to resemble war wearing a borrowed suit?

Supporters insist this was not an act of war. It was a surgical operation. Precise. Clean. Professional. The language is important, because language is how we launder violence into something more palatable. Wars are messy, expensive, and politically dangerous. “Operations,” on the other hand, sound like something that happens in a well-lit room with stainless steel instruments and a signed consent form. Venezuela, it seems, did not get to sign.

If this is what a country that doesn’t want another war does, then war has been rebranded rather than rejected. We no longer invade; we “intervene.” We no longer overthrow governments; we “remove destabilizing actors.” We no longer kidnap foreign heads of state; we “take them into custody.” The actions remain remarkably familiar, even if the vocabulary has been scrubbed for prime time.

The justification, of course, is necessity. We were told there was no choice. There never is. Necessity is the most reliable excuse in the empire’s toolbox. It bypasses debate, sidesteps international law, and frames skepticism as naïveté. You either support the mission or you don’t care about security, democracy, or whatever value happens to be useful that week.

But necessity has a curious habit of flowing in only one direction. When another country violates sovereignty, it is an outrage. When we do it, it is leadership. When they send armed forces across borders, it is aggression. When we do it, it is restraint. Peace, apparently, is defined not by the absence of force, but by who controls the narrative afterward.

There is also the matter of precedent, that tedious concept we only worry about once it’s too late. If sending elite troops into a sovereign nation to seize its leader does not constitute an act of war, then what does? If this is peace, what exactly are we trying to avoid? Tanks in the streets? Bombs on the evening news? Or merely the inconvenience of admitting that peace is not something you declare—it is something you practice.

In the end, the contradiction is the point. Calling a leader a peace-time president while applauding acts that would have once been unambiguously described as war is not confusion; it is strategy. It allows a nation to feel virtuous while behaving aggressively, to claim moral high ground while standing on someone else’s soil with a gun.

So yes, perhaps this is what a country that “doesn’t want to start another war” does now. It just doesn’t call it a war. And as long as the word is avoided, we are expected to believe that peace—however heavily armed—still exists.